The importance of communication never weighed on me so heavily as when I landed in Tokyo, Japan this February. Ironically, I had spent the ten plus hour journey from Seattle, Washington to my vacation destination reading a memoir about being an outcast from American society because the author grew up speaking only Spanish. The isolation he shared by not being proficient in the dominant language was not lost on me that trip.

Excitedly, I read news headlines about a massive snowstorm covering the island. Japan, a dream snowboarding destination for me, was apparently living up to its nickname of “Japow.” But what I didn’t realize in my nervous pre airplane boarding excitement was that too much snow meant the entire southern area would shut down. At the airport in Tokyo, my high school friend would be waiting for me, ready to guide me through the snowy cityscape, and then send me off to enjoy the snow the way God had intended: by snowboarding.

Almost a foot of snow dropped in less than 24 hours, disrupting every type of transport you can imagine. When I landed at Henada, the reality of the storm became more real. “Alison,” the message read, “there are no trains. I can’t get to you. You’re on your own.” The snow had come, which meant my translator and guide couldn’t.

Panic. Absolute and complete panic. I didn’t know much more Japanese than hai and arigato gozaimasu. I certainly couldn’t read the language, and now navigating to my hotel put me into a state of frenzy. Sweat pooled on my lower back and a sickly taste of dear-god-what-do-I-do-now covered my tongue. Deep breath. I did what I had to do- I sucked it up and asked for help.

After navigating through immigration and gathering my bags in the efficient and clean airport, I managed to find the information desk, open even this late at night and filled with friendly, helpful, mostly English speaking helpers. It’s as though the government anticipated moron Americans to just appear in their country and not speak a word of the language. I was directed how to find my accommodations, and, after struggling to check in with my concierge and get my internet connection to work so I could contact my friend Brigg, I flicked on the television for some comfort.

I anticipated this, but I hoped for something different–no English channels, of course. Always the cultural anthropologist, I was intrigued with what Japanese TV had to offer. I opened my vending machine beer and sat back to watch a live sumo wresting match, which turned into a variety show with the winner singing terribly along with ten or so young women. This was followed by commercials for toupes for women, dental surgery, and finally the Olympics.

The next morning my options were to cry in my room (which, to be honest, I nearly did) or to see the city I flew 14 hours to be in. Breakfast was served downstairs, and I noticed immediately the stares of my fellow guests. Being in a more residential area than tourist area (it was cheap and on the subway line), I happened to be the only non-business person. And the only non-Japanese person. And the only woman. I could feel the awkward sideways glances as I made my coffee and filled my plate halfway with a hard boiled egg and unfamiliar pastry. (The egg, by the way, turned out the be the first of many, an obsession with Japanese eggs I will resume later).

I nabbed a subway map as I nervously trotted out the door. One of the day concierge spoke just enough English to point to the temple I wished to see. The girls at the front desk tried with supreme patience and kindness to help me; we even broke down once and used GoogleTranslate in desperation. My fear wasn’t subways- I’d been on subways a million times in Paris and DC and New York and London and Portland. But there, the languages weren’t kanji, and there I spoke the languages. Terrified I would get on a train and never return, I had to have faith that somehow I would find my way.

After fighting with the ticket machine (I still to this day have no idea what pass to purchase for the MAX in Portland–how would I know which to buy in Japan?), I ventured forth, thankful that signage now has English “subtitles,” generally spelled correctly and everything. I headed for the Asakusa area hoping to play tourist for the day going to the temple, the Sky Tree, the bay, and other various touristy areas.

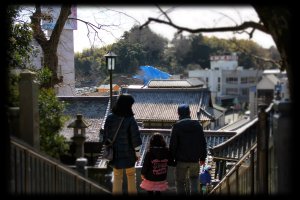

Once emerging from the subway, I meandered the city until I found the temple in question. Booths lined the way up to the temple steps, selling all sorts of goods and foods. I stopped for a sesame bun, ordering by pointing and smiling. The man behind the counter understood, though unamused with me, and took my money quickly. I remembered reading that Japanese don’t eat and walk (unlike us fast-paced Americans) so I paused at an orange tree and statue to eat. I wish I knew what the statue represented, but it held some significance regarding the orange tree. I think.

The grounds were beautiful, and occasionally I would catch a family quietly speaking English, or a translator guiding a group and explaining the sites. I leaned in, gleaning what I could, soaking in the only familiar language I could, but otherwise meandered through ancient history and a culture so different from anything I’d ever known. Red flags waved in the snowy breeze proclaiming something of importance, but what I had no idea. I spent my time photographing the Buddah statue and the pagoda and the memorials and the bells and the water features. It was afternoon by the time I realized I hadn’t truly spoken in hours.

Back on the trains I felt even more of an outsider. I had never been so outside of my comfort zone, or my cultural zone. The Japanese tend to be silent in their public transportations, which lent me more time to consider my surroundings, but also more time to feel completely isolated. The subway trains in Tokyo, especially in the center districts, seem to be constantly packed with locals. I saw only a few other tourists mixed in, but each disappeared into new destinations. The only English I overheard was from announcements for the upcoming location.

After a boat tour and finding the Asahi brewery, I found my way to the shopping district. The streets close to autos on Sunday afternoons, allowing pedestrian traffic to take over the area. High-end shopping lined the quiet, snow-filled streets, only separated by noodle houses and other tourist-minded restaurants. I found a Yoshinoya, but couldn’t bring myself to eat there. Instead, I manged at a quiet Japanese noodle house underground, listening for longer than my meal lasted to the American and Brit talking over their dinner. I missed conversation so much, I was tempted to just jump into their table and beg for words.

Language is what connects us, but is also what isolates us. I cannot imagine how difficult it must be to live in a country where you don’t speak the language fluently enough to communicate with the outside world, watching families and groups gather and yet you stand alone, unable to connect to others.

When I finally left Tokyo for Sapporo the next morning, I stood in a long line for check in while the air line representatives shouted long, commanding sentences at us, grabbing people in line who raised their hands intermittently, whilst I had no clue what was happening. I just stayed in line and hoped. I would never change my experience in Japan– my lack of language has infinitely changed how I perceive the world, and how thankful I am for being able to communicate.

It is foolish and arrogant for anyone to assume a foreign country will speak English. Though it is a common language, it is not the most used language nor the only language. The Japanese were very accommodating, but I am humbled by the experience, and am currently investing in Japanese language courses, because I do plan to go back next year.

It’s awesome to pay a visit this web site and reading the views of all friends about this post, while

I am also eager of getting know-how.